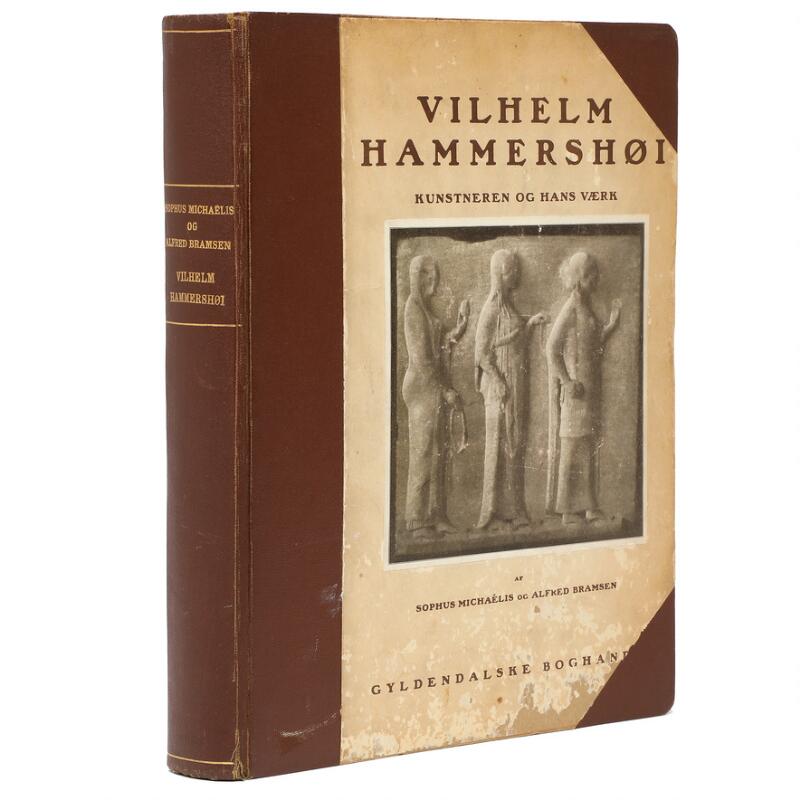

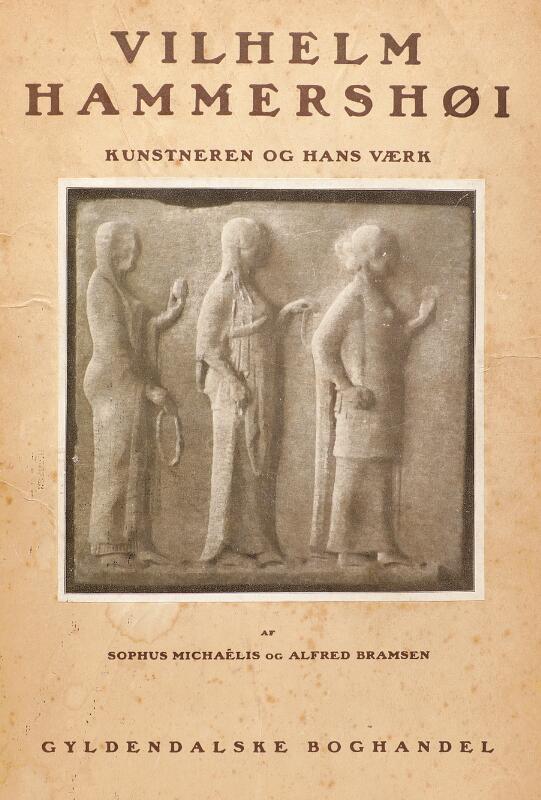

Vilhelm Hammershøi (b. Copenhagen 1864, d. s.p. 1916) “Morgen-Toilette”. Morning toilette. 1914. Unsigned. Oil on canvas. 87×73 cm. Alfred Bramsen, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vilhelm Hammershøi “Vilhelm Hammershøi. Kunstneren og hans værk”, 1918, no. 375: “Morgen-Toilette. Forarbejde til Nr. 374. Mindre udført. Her findes ingen Fajance-Skaal.” (Morning Toilette. Study for No. 374. Less finished. Here is no faience bowl). Susanne Meyer-Abich, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vilhelm Hammershøi in “Vilhelm Hammershøi: Das Malerische Werk", 1995, no. 373. Literature: Annette Rosenvold Hvidt and Gertrud Oelsner, “Vilhelm Hammershøi, på sporet af det åbne billede”, 2018, mentioned p. 480 and ill. p. 478. Provenance: The artist's estate auction 1916 no. 10. The artist's wife Ida Hammershøi (1918). Bruun Rasmussen auction 18, 1951 no. 64. Bruun Rasmussen auction 801, 2009 no. 103, ill. p. 104. In the section entitled “Morgentoilette: en ny begyndelse” (Morning toilette: a new beginning) (pp. 310 – 314) of the book “Hammershøi. Værk og liv” (1990) (Hammershøi. Works and life), Poul Vad describes how he sees the work “Morgentoilette” as an expression of a new artistic beginning for Hammershøi – an artistic breakthrough in his works in the form of, for example, a break with the plane-parallel spaces so characteristic of his works up to this point, in favour of greater intimacy and plasticity. “In 1914, with Ida as his model, Hammershøi embarked on a large figure painting that he would never complete. It pointed to rich, new possibilities in his art, but as it remained unfinished and had no successors, it would become the work that rounded it all off, the endpoint of the development that began with the portrait of his sister in 1885 – after a 180-degree turn.”[….] “If we compare it with the portrait of his sister from 1885, they seem to correspond to each other point by point – as opposites: back-facing versus forward-facing displacement to the left versus displacement to the right white, short-sleeved blouse with an open neckline revealing a broad upper body versus a black, long-sleeved, high-necked dress on a body that narrows upwards towards the head increasing movement in the body and strong, raised, active arms and hands versus decreasing movement and delicate, passive, nervous arms and hands active, physical activity in all dimensions of the room: width, height, depth, versus passive vegetative “inactivity”.” (p. 310). “The hand raised to the head in the process of fixing the hair had previously captivated Hammershøi as a plastic motif.” […] “Only now has he felt equipped to take it up as a central motif in a large format – adding a new dimension to both his portrayal of women and his painterly universe in the process. Instead of a static figure and the distance-creating, frontally perceived, plane-parallel space, here we have a figure displaced depth-wise, performing two movements at once and expanding the plane with her energy. Hammershøi had never painted like this before. The sensuality and intimacy in his portrayal of women, which in the early pictures was associated with almost total immobility – both because the woman was motionless and because she was bound visually to the plane-parallel layout – has here a far more direct, less abstract character. Indeed, in the subject herself – the not yet fully dressed woman setting her hair – there is a new intimacy to Hammershøi’s art. It is as if Hammershøi, who had painted Ida’s neck between the neckline of the dress and the base of her upswept hair with such fascination, has crossed a line to capture the moment when she shyly lifts her hair away from her neck with her hand as if exposed.” (p. 311). Hammershøi died in 1915 and did not therefore further these interesting new artistic explorations. (Please note that the painting that Vad analyses is no. 374 in Bramsen’s catalogue raisonné. Nos. 374 and 375 (the present painting) closely resemble each other in motif, com

Condition

Vilhelm Hammershøi (b. Copenhagen 1864, d. s.p. 1916) “Morgen-Toilette”. Morning toilette. 1914. Unsigned. Oil on canvas. 87×73 cm. Alfred Bramsen, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vilhelm Hammershøi “Vilhelm Hammershøi. Kunstneren og hans værk”, 1918, no. 375: “Morgen-Toilette. Forarbejde til Nr. 374. Mindre udført. Her findes ingen Fajance-Skaal.” (Morning Toilette. Study for No. 374. Less finished. Here is no faience bowl). Susanne Meyer-Abich, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vilhelm Hammershøi in “Vilhelm Hammershøi: Das Malerische Werk", 1995, no. 373. Literature: Annette Rosenvold Hvidt and Gertrud Oelsner, “Vilhelm Hammershøi, på sporet af det åbne billede”, 2018, mentioned p. 480 and ill. p. 478. Provenance: The artist's estate auction 1916 no. 10. The artist's wife Ida Hammershøi (1918). Bruun Rasmussen auction 18, 1951 no. 64. Bruun Rasmussen auction 801, 2009 no. 103, ill. p. 104. In the section entitled “Morgentoilette: en ny begyndelse” (Morning toilette: a new beginning) (pp. 310 – 314) of the book “Hammershøi. Værk og liv” (1990) (Hammershøi. Works and life), Poul Vad describes how he sees the work “Morgentoilette” as an expression of a new artistic beginning for Hammershøi – an artistic breakthrough in his works in the form of, for example, a break with the plane-parallel spaces so characteristic of his works up to this point, in favour of greater intimacy and plasticity. “In 1914, with Ida as his model, Hammershøi embarked on a large figure painting that he would never complete. It pointed to rich, new possibilities in his art, but as it remained unfinished and had no successors, it would become the work that rounded it all off, the endpoint of the development that began with the portrait of his sister in 1885 – after a 180-degree turn.”[….] “If we compare it with the portrait of his sister from 1885, they seem to correspond to each other point by point – as opposites: back-facing versus forward-facing displacement to the left versus displacement to the right white, short-sleeved blouse with an open neckline revealing a broad upper body versus a black, long-sleeved, high-necked dress on a body that narrows upwards towards the head increasing movement in the body and strong, raised, active arms and hands versus decreasing movement and delicate, passive, nervous arms and hands active, physical activity in all dimensions of the room: width, height, depth, versus passive vegetative “inactivity”.” (p. 310). “The hand raised to the head in the process of fixing the hair had previously captivated Hammershøi as a plastic motif.” […] “Only now has he felt equipped to take it up as a central motif in a large format – adding a new dimension to both his portrayal of women and his painterly universe in the process. Instead of a static figure and the distance-creating, frontally perceived, plane-parallel space, here we have a figure displaced depth-wise, performing two movements at once and expanding the plane with her energy. Hammershøi had never painted like this before. The sensuality and intimacy in his portrayal of women, which in the early pictures was associated with almost total immobility – both because the woman was motionless and because she was bound visually to the plane-parallel layout – has here a far more direct, less abstract character. Indeed, in the subject herself – the not yet fully dressed woman setting her hair – there is a new intimacy to Hammershøi’s art. It is as if Hammershøi, who had painted Ida’s neck between the neckline of the dress and the base of her upswept hair with such fascination, has crossed a line to capture the moment when she shyly lifts her hair away from her neck with her hand as if exposed.” (p. 311). Hammershøi died in 1915 and did not therefore further these interesting new artistic explorations. (Please note that the painting that Vad analyses is no. 374 in Bramsen’s catalogue raisonné. Nos. 374 and 375 (the present painting) closely resemble each other in motif, com

Condition

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen