Property of a New York Collector

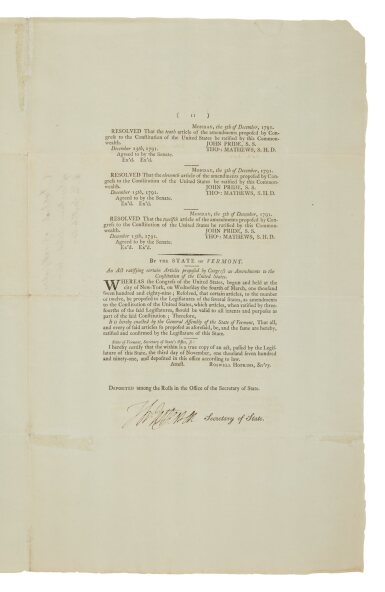

United States ConstitutionFirst-day publication of the Constitution:

Plan of the New Federal Government. We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America. … Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present, the 17th day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the twelfth. Philadelphia: The Independent Gazetteer, or, the Chronicle of Freedom, Printed (daily) by Eleazer Oswald, at the Coffee-House, Volume VI, Number 553, Wednesday, 19 September 1787

4-page large 4to newspaper issue (294 x 240 mm) on a bifolium, text printed in three columns, the Constitution (including the roster of its Signers, the two resolutions of the Convention adopted on 17 September recommending the procedures for ratification and for the establishment of government under the Constitution by the Confederation Congress, and George Washington’s influential cover letter of the same date to Arthur St. Clair, president of Congress) dominates the issue, occupying the two right columns of the first page, the entirety of the second page, and most of the two left columns of the third page, woodcut ship vignettes among the advertisements; some light browning and very minor foxing, central fold expertly repaired.

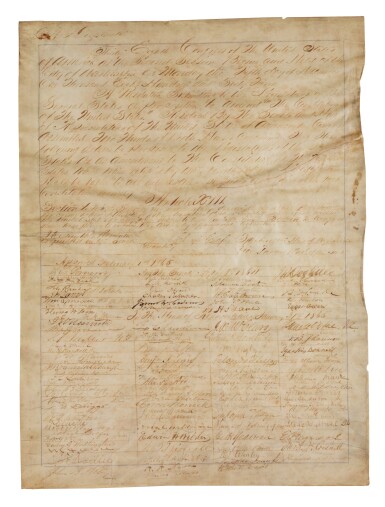

Accompanied by a long run of The Independent Gazetteer, 10 October 1786 (Volume VI, Number 260)–3 December 1787 (Volume VII, Number 617), comprising 357 daily issues totaling more than 1,400 pages, with some duplicate issues; a few scattered pages lacking or defective, some browning, staining, and foxing, scattered marginal tears. Disbound, with many issues weakened or separated at central fold.

A scarce first-day publication of the United States Constitution, now the longest continuing charter of a national government in the world and "the product of a revolution in political thought at least as important and far-reaching as the winning of American independence from Great Britain [and] the culmination of the intellectual ferment and political experimentation in the new republic" (Richard B. Bernstein, Are We to Be a Nation?).

Revolutionary-era Americans were a constitution-making people. On several occasions during the debate over the ratification of the Constitution of 1787, it was said that Americans knew more about the nature of government and liberty than any other people in the world. During the Revolutionary era, Americans wrote more than a dozen state constitutions, two federal constitutions, many amendments to these constitutions, and ordinances establishing the government for federal territories and the process for them to attain statehood.

Americans realized that if they succeeded in obtaining their independence, they would need to create new governments to replace the British imperial authority and the colonial governments that were formed under charters that had been granted by the king or by colonial proprietors such as William Penn. Thus, in May 1776, even before the approval of the Declaration of Independence, the Second Continental Congress recommended that the colonies replace their charters with constitutions amenable to the people. The new state constitutions were drafted and approved by provincial assemblies elected by the people. All of the governments were said to originate from the people, were founded in the social compact, and were instituted solely for the good of the whole.

The germ of the Constitution was, fittingly, contained in the same congressional resolution that led directly to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. On 7 June 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee introduced in the Second Continental Congress a resolution stating "That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved." Lee’s resolution further averred "That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation." Just five days after Lee’s proposal was voiced, a committee of one delegate from each colony was appointed to draft a plan. Exactly one month after its appointment, 12 July 1776, the committee, chaired by John Dickinson, proposed for debate "Articles of confederation and perpetual union" among the thirteen states.But the exigencies of war and the approach of the British to Philadelphia suspended the debate, and it was not until 15 November 1777 that Congress—by then sitting in York, Pennsylvania—adopted the Articles of Confederation and sent them to the various state legislatures, together with a circular letter urging their ratification, but the Articles were not formally ratified until 1 March 1781. The Articles provided that the states retained their sovereignty, freedom, and independence while Congress was limited to those powers expressly delegated to it in the Articles. Article XIII, however, did provide the semblance of a supremacy clause to Congress, but that body was given no coercive power to enforce state compliance. Thus, the emphasis on individual states’ rights in this "firm league of friendship" was doomed to fracture once the principal goal of the alliance had been achieved.

Despite its insufficiencies, as the first written constitution of the United States, the Articles of Confederation cannot be dismissed as entirely unsuccessful since it had yoked the individual states together in a "confederacy for securing the freedom, sovereignty, and independence of the United States" and offered a basis for what would become the Constitution as we know it.

But just as the country seemed poised to splinter, Congress resolved on 21 February 1787 that "it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a convention of delegates who shall have been appointed by the several states be held at Philadelphia for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation and reporting to Congress and the several legislatures such alterations and provisions therein as shall when agreed to in Congress and confirmed by the states render the federal constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union."

This resolution took the form of the Constitutional Convention, which led to the "“Miracle at Philadelphia," when the delegates determined that the Articles of Confederation were going to be overthrown, rather than simply amended. Meeting in ostensible secret from May through September, the delegates crafted a charter that the vast majority supported. Perhaps the best justification for the adoption of the Constitution was given by Benjamin Franklin "I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best."

The first printing of the Constitution was done by John Dunlap and David Claypoole, the official printers to the Convention, likely working through the evening of 17 September, in an edition of 500 copies (of which fourteen are known to survive) for the use of the delegates only. The pair had earlier produced two working drafts of the text, printed on rectos only, for the Committee of Detail and the Committee of Style. The first printing of the Constitution also appended to the Constitution proper two resolutions of the Convention adopted on 17 September recommending the procedures for ratification and for the establishment of government under the Constitution by the Confederation Congress. To the first printing of the Constitution, Dunlap and Claypoole also added Washington’s influential cover letter of the same date to the president of Congress. The entire cover letter—as here—usually accompanied early printings of the Constitution, indicating that Washington strongly supported ratification. Excerpts from the letter, particularly the "spirit of amity" clause, were widely quoted in political essays during the ratification debate.

Copies of the Official Edition were submitted to the Confederation Congress and distributed to the Convention delegates for use at their discretion. Many delegates dispersed their copies to other statesmen and colleagues. And many copies ended up in Philadelphia newspaper shops—and in other printing establishments around the country, where they served as the copytext for the numerous regional printings of the Constitution that quickly appeared newspapers, magazines, broadsides, pamphlets, and almanacs during the public debate over ratification.

The morning of Wednesday, 19 September, the Constitution was published in five Philadelphia newspapers: in addition to The Independent Gazetteer, the charter appeared in The Pennsylvania Journal; and the Weekly Advertiser; The Freeman's Journal, or, the North-American Intelligencer; The Pennsylvania Gazette; and The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser. Because the Packet was published by Dunlap and Claypoole, who had the text of the Constitution standing in type, pride of place has traditionally been given to their newspaper, although there is no way to know which paper actually hit the streets first. All five are considered first publications, with surviving copies of the Packet the most common.

The accompanying run of issues of The Independent Gazetteer; or, the Chronicle of Freedom—all bearing as part of the masthead an excerpt from the Pennsylvania Bill of Rights guaranteeing freedom of the press—provides vital contemporary context for the Constitution, before, during, and after the convention. Although the newspaper published several articles praising the Federal Convention in the summer of 1787 and printed both Federalist and Antifederalist essays in the first two months of debate on the proposed Constitution, by November 1787, it had become strongly Antifederalist.

These issues also detail the unfolding drama of Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, the initial success of which demonstrated the weakness of the Articles of Confederation and the need for a stronger federal government. Benjamin Franklin George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton each appear, both in connection with their participation in the Constitutional Convention and in other contexts.

The Independent Gazetteer contained more original Antifederalist pieces than any other newspaper. Some were simply abusive and disparaging of Federalists and the proposed Constitution, but others were calm and well-reasoned. The newspaper published three major series of Antifederalist essays. The first was a series of eighteen essays written by Samuel Bryan (1759–1821) using the pseudonym "Centinel," published between 5 October 1787 and 9 April 1788. While Bryan wrote most, his father and Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice George Bryan (1731–1791) and Independent Gazetteer editor Eleazar Oswald may have written or contributed to some of the essays.

The second was a series of eight articles written by "An Old Whig," likely George Bryan and state senator and future Congressman John Smilie (1742–1812), that appeared between October 1787 and February 1788. Benjamin Workman, an instructor of mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania and a recent Irish immigrant chose the pseudonym "Philadelphiensis" for the third series of twelve Antifederalist essays that appeared between November 1787 and March 1788.

This series of issues includes the first installments of all three series—three of the first four essays by "Centinel"; the first seven articles by "An Old Whig"; and the first two installments by "Philadelphiensis." This run also includes numerous other Federalist and Antifederalist essays exploring all parts of the proposed Constitution.

Many important news articles and editorial opinion pieces appear throughout the run, including:

¶ 25 October 1786: an essay on the Plan for a New Federal Government (p. 3/c. 2):"It must be obvious to every man, who will give himself the trouble to reflect a moment on the present system of the foederal government of the United States of North-America, that it is so wretchedly defective, that unless some remedy be soon applied, it must soon fall to pieces; and the confusion which must inevitably ensue, will be productive of the most fatal consequences."

¶ 6 November 1786: announcement of Benjamin Franklin’s re-election as president of Pennsylvania by the legislature and supreme executive council (p. 3/c. 1).

¶ 15 December 1786: Virginia act providing for the election by the legislature of seven commissioners to a convention to recommend alterations and further provisions "as may be necessary to render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of the Union" (p. 2/c. 2).

¶ 12 February 1787: North Carolina provides for election by General Assembly of five deputies to attend Convention in May in Philadelphia; elects Governor Richard Caswell, Alexander Martin, William R. Davie, Richard Dobbs Spaight, and Willie Jones (p. 3/c, 2–3); the North Carolina delegates to the Constitutional Convention were actually Spaight, Davie, Martin, William Blount, and Hugh Williamson.

¶ 13 February 1787: Captain Luke Day’s 25 January demand for the surrender of government forces at Springfield in Shays’ Rebellion, and correspondence between General Benjamin Lincoln and Daniel Shays (p. 2/c. 2–3)

¶ 2 March 1787: Congressional resolution of February 27 calling for a Federal Convention to convene in May 1787 in Philadelphia (p. 2/c. 3): "Resolved, That in the opinion of Congress, it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a Convention of Delegates, who shall have been appointed by the several states, be held at Philadelphia, for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation, and reporting to Congress and the several Legislatures, such alterations and provisions therein, as shall, when agreed to in Congress, and confirmed by the states, render the Federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union."

¶ 14 May 1787: George Washington arrived in Philadelphia on 13 May as one of the Virginia delegates to the Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 3): "His arrival was announced by a salute of the United States from the Train Artillery; He was escorted from Chester by the city Light-Dragoons; and has taken apartments at Mrs. House’s, one of the most genteel boarding houses in this city."

¶ 18 May 1787: Letter from Newport, Rhode Island, about state’s absence from Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 1): "The Members from Providence and this town brought on the question, Whether they should send Members to the Convention at Philadelphia or not? It passed the Lower House by a majority of two; and when brought before the Upper House, there was a majority of two to one against sending them—therefore we will not be represented, and, I suppose, finally, be put out of the Union."

¶ 26 May 26 1787: Federal Convention meets in Philadelphia (p. 2/c. 2): "Yesterday, at the State-House in this city, seven states were fully represented in Convention: These forming a quorum, they proceeded to the choice of a President, and his Excellency General Washington was unanimously elected to that important station."

¶ 27 June 1787: Reflections on Federal Convention (p/ 2/c. 3–p. 3/c. 1): "The present Federal Convention, says a correspondent, is happily composed of men who are qualified from education, experience and profession for the great business assigned to them. The principles, the administration or executive duties of government will be pointed out by those gentlemen who have filled or who now fill the offices of first Magistrate in several of the States—while the commercial interests of America will be faithfully represented and ably explained by the mercantile part of the Convention. These gentlemen are assembled at a most fortunate period—in the midst of peace—with leisure to explore the perfections or defects of all the governments that ever existed—with passions uncontrouled by the resentments and prejudices kindled by the late war—and with a variety of experiments before them of the feebleness, tyranny, and licentiousness, of our American forms of government. Under such circumstances, it will not be difficult for them to frame a Federal Constitution that will suit our country. The present Confederation may be compared to a hut or tent, accommodated to the emergencies of war—but it is now time to erect a castle of durable materials, with a tight roof and substantial bolts and bars to secure our persons and property from violence, and external injuries of all kinds. May this building rise like a pyramid upon the broad basis of the people! and may they have wisdom to see that if they delegate a little more power to their Rulers, the more liberty they will possess themselves, provided they take care to secure their sovereignty and importance by frequent elections, and rotation of offices."

¶ 5 July 1787: proclamation by Massachusetts Governor John Hancock offering clemency to repentant Shays’ Rebels (p. 2/c. 1); Hancock’s message to the General Court (p. 2/c. 1–2).

¶ 19 July 1787: celebration of Independence Day at Yale University, including a toast to the "Federal Convention" (p. 2/c. 1).

¶ 23 July 1787: full printing of An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio (p. 2/c.1–p. 3/c. 1); New Hampshire selects Benjamin West to represent the state in the Confederation Congress, and together with John Langdon John Pickering, and Nicholas Gilman, to represent the state at the Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 1).

¶ 9 August 1787: correspondence from Petersburg, Virginia (p. 2/c. 3): "The Grand Federal Convention it is hoped will act wisely, for on their determination alone, and our acquiescence, depends our future happiness and prosperity; and if there lives a man equal to so arduous a task, it is a Washington."

¶ 17 August 1787: letter from "Meanwell" to Editor Eleazar Oswald (p. 3/c. 2): We have now sitting a Convention, which, I am persuaded, would have done honor to the states of Greece and Rome in their highest glory. Abstracted from their virtue, they have every additional tie of character, property and interest, that can bind men to be true to us and to themselves. Every honest man will readily agree with me in opinion, that our future political safety and happiness depend on the result of their present deliberations. This needs no illustration. I would therefore, through the channel of your paper, submit one query to the serious consideration of that honorable body, viz. Whether it would not be improper, at this crisis, [not] to dissolve themselves entirely, but rather to adjourn to meet again, if need be, at some future period?"

¶ 18 September 1787: notice of the closing of the Constitutional Convention (p. 3/c. 2).

¶ 26 September 1787: a member of Congress calls for an early Pennsylvania state convention to ratify the Constitution (p. 3/c. 2); reactions of various states to the proposed new frame of government (p. 3/c. 2–3).

¶ 1October 1787: Congressional resolution transmitting the Federal Convention’s report to the state legislatures (p. 2/c. 3); resolutions by the Pennsylvania General Assembly regarding selection of state convention delegates (p. 2/c. 3); an act specifying a new oath of allegiance for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (p. 3/c. 1–2).

Sotheby's is grateful to Seth Kaller for his assistance with this description.

PROVENANCE:Department of State (ink stamp, dated 23 June 1887 on first issue of the run) — Irwin T. Hughes (mid-twentieth-century inscription on old endpaper)

Property of a New York Collector

United States ConstitutionFirst-day publication of the Constitution:

Plan of the New Federal Government. We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America. … Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present, the 17th day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the twelfth. Philadelphia: The Independent Gazetteer, or, the Chronicle of Freedom, Printed (daily) by Eleazer Oswald, at the Coffee-House, Volume VI, Number 553, Wednesday, 19 September 1787

4-page large 4to newspaper issue (294 x 240 mm) on a bifolium, text printed in three columns, the Constitution (including the roster of its Signers, the two resolutions of the Convention adopted on 17 September recommending the procedures for ratification and for the establishment of government under the Constitution by the Confederation Congress, and George Washington’s influential cover letter of the same date to Arthur St. Clair, president of Congress) dominates the issue, occupying the two right columns of the first page, the entirety of the second page, and most of the two left columns of the third page, woodcut ship vignettes among the advertisements; some light browning and very minor foxing, central fold expertly repaired.

Accompanied by a long run of The Independent Gazetteer, 10 October 1786 (Volume VI, Number 260)–3 December 1787 (Volume VII, Number 617), comprising 357 daily issues totaling more than 1,400 pages, with some duplicate issues; a few scattered pages lacking or defective, some browning, staining, and foxing, scattered marginal tears. Disbound, with many issues weakened or separated at central fold.

A scarce first-day publication of the United States Constitution, now the longest continuing charter of a national government in the world and "the product of a revolution in political thought at least as important and far-reaching as the winning of American independence from Great Britain [and] the culmination of the intellectual ferment and political experimentation in the new republic" (Richard B. Bernstein, Are We to Be a Nation?).

Revolutionary-era Americans were a constitution-making people. On several occasions during the debate over the ratification of the Constitution of 1787, it was said that Americans knew more about the nature of government and liberty than any other people in the world. During the Revolutionary era, Americans wrote more than a dozen state constitutions, two federal constitutions, many amendments to these constitutions, and ordinances establishing the government for federal territories and the process for them to attain statehood.

Americans realized that if they succeeded in obtaining their independence, they would need to create new governments to replace the British imperial authority and the colonial governments that were formed under charters that had been granted by the king or by colonial proprietors such as William Penn. Thus, in May 1776, even before the approval of the Declaration of Independence, the Second Continental Congress recommended that the colonies replace their charters with constitutions amenable to the people. The new state constitutions were drafted and approved by provincial assemblies elected by the people. All of the governments were said to originate from the people, were founded in the social compact, and were instituted solely for the good of the whole.

The germ of the Constitution was, fittingly, contained in the same congressional resolution that led directly to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. On 7 June 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee introduced in the Second Continental Congress a resolution stating "That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved." Lee’s resolution further averred "That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation." Just five days after Lee’s proposal was voiced, a committee of one delegate from each colony was appointed to draft a plan. Exactly one month after its appointment, 12 July 1776, the committee, chaired by John Dickinson, proposed for debate "Articles of confederation and perpetual union" among the thirteen states.But the exigencies of war and the approach of the British to Philadelphia suspended the debate, and it was not until 15 November 1777 that Congress—by then sitting in York, Pennsylvania—adopted the Articles of Confederation and sent them to the various state legislatures, together with a circular letter urging their ratification, but the Articles were not formally ratified until 1 March 1781. The Articles provided that the states retained their sovereignty, freedom, and independence while Congress was limited to those powers expressly delegated to it in the Articles. Article XIII, however, did provide the semblance of a supremacy clause to Congress, but that body was given no coercive power to enforce state compliance. Thus, the emphasis on individual states’ rights in this "firm league of friendship" was doomed to fracture once the principal goal of the alliance had been achieved.

Despite its insufficiencies, as the first written constitution of the United States, the Articles of Confederation cannot be dismissed as entirely unsuccessful since it had yoked the individual states together in a "confederacy for securing the freedom, sovereignty, and independence of the United States" and offered a basis for what would become the Constitution as we know it.

But just as the country seemed poised to splinter, Congress resolved on 21 February 1787 that "it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a convention of delegates who shall have been appointed by the several states be held at Philadelphia for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation and reporting to Congress and the several legislatures such alterations and provisions therein as shall when agreed to in Congress and confirmed by the states render the federal constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union."

This resolution took the form of the Constitutional Convention, which led to the "“Miracle at Philadelphia," when the delegates determined that the Articles of Confederation were going to be overthrown, rather than simply amended. Meeting in ostensible secret from May through September, the delegates crafted a charter that the vast majority supported. Perhaps the best justification for the adoption of the Constitution was given by Benjamin Franklin "I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best."

The first printing of the Constitution was done by John Dunlap and David Claypoole, the official printers to the Convention, likely working through the evening of 17 September, in an edition of 500 copies (of which fourteen are known to survive) for the use of the delegates only. The pair had earlier produced two working drafts of the text, printed on rectos only, for the Committee of Detail and the Committee of Style. The first printing of the Constitution also appended to the Constitution proper two resolutions of the Convention adopted on 17 September recommending the procedures for ratification and for the establishment of government under the Constitution by the Confederation Congress. To the first printing of the Constitution, Dunlap and Claypoole also added Washington’s influential cover letter of the same date to the president of Congress. The entire cover letter—as here—usually accompanied early printings of the Constitution, indicating that Washington strongly supported ratification. Excerpts from the letter, particularly the "spirit of amity" clause, were widely quoted in political essays during the ratification debate.

Copies of the Official Edition were submitted to the Confederation Congress and distributed to the Convention delegates for use at their discretion. Many delegates dispersed their copies to other statesmen and colleagues. And many copies ended up in Philadelphia newspaper shops—and in other printing establishments around the country, where they served as the copytext for the numerous regional printings of the Constitution that quickly appeared newspapers, magazines, broadsides, pamphlets, and almanacs during the public debate over ratification.

The morning of Wednesday, 19 September, the Constitution was published in five Philadelphia newspapers: in addition to The Independent Gazetteer, the charter appeared in The Pennsylvania Journal; and the Weekly Advertiser; The Freeman's Journal, or, the North-American Intelligencer; The Pennsylvania Gazette; and The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser. Because the Packet was published by Dunlap and Claypoole, who had the text of the Constitution standing in type, pride of place has traditionally been given to their newspaper, although there is no way to know which paper actually hit the streets first. All five are considered first publications, with surviving copies of the Packet the most common.

The accompanying run of issues of The Independent Gazetteer; or, the Chronicle of Freedom—all bearing as part of the masthead an excerpt from the Pennsylvania Bill of Rights guaranteeing freedom of the press—provides vital contemporary context for the Constitution, before, during, and after the convention. Although the newspaper published several articles praising the Federal Convention in the summer of 1787 and printed both Federalist and Antifederalist essays in the first two months of debate on the proposed Constitution, by November 1787, it had become strongly Antifederalist.

These issues also detail the unfolding drama of Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, the initial success of which demonstrated the weakness of the Articles of Confederation and the need for a stronger federal government. Benjamin Franklin George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton each appear, both in connection with their participation in the Constitutional Convention and in other contexts.

The Independent Gazetteer contained more original Antifederalist pieces than any other newspaper. Some were simply abusive and disparaging of Federalists and the proposed Constitution, but others were calm and well-reasoned. The newspaper published three major series of Antifederalist essays. The first was a series of eighteen essays written by Samuel Bryan (1759–1821) using the pseudonym "Centinel," published between 5 October 1787 and 9 April 1788. While Bryan wrote most, his father and Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice George Bryan (1731–1791) and Independent Gazetteer editor Eleazar Oswald may have written or contributed to some of the essays.

The second was a series of eight articles written by "An Old Whig," likely George Bryan and state senator and future Congressman John Smilie (1742–1812), that appeared between October 1787 and February 1788. Benjamin Workman, an instructor of mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania and a recent Irish immigrant chose the pseudonym "Philadelphiensis" for the third series of twelve Antifederalist essays that appeared between November 1787 and March 1788.

This series of issues includes the first installments of all three series—three of the first four essays by "Centinel"; the first seven articles by "An Old Whig"; and the first two installments by "Philadelphiensis." This run also includes numerous other Federalist and Antifederalist essays exploring all parts of the proposed Constitution.

Many important news articles and editorial opinion pieces appear throughout the run, including:

¶ 25 October 1786: an essay on the Plan for a New Federal Government (p. 3/c. 2):"It must be obvious to every man, who will give himself the trouble to reflect a moment on the present system of the foederal government of the United States of North-America, that it is so wretchedly defective, that unless some remedy be soon applied, it must soon fall to pieces; and the confusion which must inevitably ensue, will be productive of the most fatal consequences."

¶ 6 November 1786: announcement of Benjamin Franklin’s re-election as president of Pennsylvania by the legislature and supreme executive council (p. 3/c. 1).

¶ 15 December 1786: Virginia act providing for the election by the legislature of seven commissioners to a convention to recommend alterations and further provisions "as may be necessary to render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of the Union" (p. 2/c. 2).

¶ 12 February 1787: North Carolina provides for election by General Assembly of five deputies to attend Convention in May in Philadelphia; elects Governor Richard Caswell, Alexander Martin, William R. Davie, Richard Dobbs Spaight, and Willie Jones (p. 3/c, 2–3); the North Carolina delegates to the Constitutional Convention were actually Spaight, Davie, Martin, William Blount, and Hugh Williamson.

¶ 13 February 1787: Captain Luke Day’s 25 January demand for the surrender of government forces at Springfield in Shays’ Rebellion, and correspondence between General Benjamin Lincoln and Daniel Shays (p. 2/c. 2–3)

¶ 2 March 1787: Congressional resolution of February 27 calling for a Federal Convention to convene in May 1787 in Philadelphia (p. 2/c. 3): "Resolved, That in the opinion of Congress, it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a Convention of Delegates, who shall have been appointed by the several states, be held at Philadelphia, for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation, and reporting to Congress and the several Legislatures, such alterations and provisions therein, as shall, when agreed to in Congress, and confirmed by the states, render the Federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union."

¶ 14 May 1787: George Washington arrived in Philadelphia on 13 May as one of the Virginia delegates to the Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 3): "His arrival was announced by a salute of the United States from the Train Artillery; He was escorted from Chester by the city Light-Dragoons; and has taken apartments at Mrs. House’s, one of the most genteel boarding houses in this city."

¶ 18 May 1787: Letter from Newport, Rhode Island, about state’s absence from Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 1): "The Members from Providence and this town brought on the question, Whether they should send Members to the Convention at Philadelphia or not? It passed the Lower House by a majority of two; and when brought before the Upper House, there was a majority of two to one against sending them—therefore we will not be represented, and, I suppose, finally, be put out of the Union."

¶ 26 May 26 1787: Federal Convention meets in Philadelphia (p. 2/c. 2): "Yesterday, at the State-House in this city, seven states were fully represented in Convention: These forming a quorum, they proceeded to the choice of a President, and his Excellency General Washington was unanimously elected to that important station."

¶ 27 June 1787: Reflections on Federal Convention (p/ 2/c. 3–p. 3/c. 1): "The present Federal Convention, says a correspondent, is happily composed of men who are qualified from education, experience and profession for the great business assigned to them. The principles, the administration or executive duties of government will be pointed out by those gentlemen who have filled or who now fill the offices of first Magistrate in several of the States—while the commercial interests of America will be faithfully represented and ably explained by the mercantile part of the Convention. These gentlemen are assembled at a most fortunate period—in the midst of peace—with leisure to explore the perfections or defects of all the governments that ever existed—with passions uncontrouled by the resentments and prejudices kindled by the late war—and with a variety of experiments before them of the feebleness, tyranny, and licentiousness, of our American forms of government. Under such circumstances, it will not be difficult for them to frame a Federal Constitution that will suit our country. The present Confederation may be compared to a hut or tent, accommodated to the emergencies of war—but it is now time to erect a castle of durable materials, with a tight roof and substantial bolts and bars to secure our persons and property from violence, and external injuries of all kinds. May this building rise like a pyramid upon the broad basis of the people! and may they have wisdom to see that if they delegate a little more power to their Rulers, the more liberty they will possess themselves, provided they take care to secure their sovereignty and importance by frequent elections, and rotation of offices."

¶ 5 July 1787: proclamation by Massachusetts Governor John Hancock offering clemency to repentant Shays’ Rebels (p. 2/c. 1); Hancock’s message to the General Court (p. 2/c. 1–2).

¶ 19 July 1787: celebration of Independence Day at Yale University, including a toast to the "Federal Convention" (p. 2/c. 1).

¶ 23 July 1787: full printing of An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio (p. 2/c.1–p. 3/c. 1); New Hampshire selects Benjamin West to represent the state in the Confederation Congress, and together with John Langdon John Pickering, and Nicholas Gilman, to represent the state at the Federal Convention (p. 3/c. 1).

¶ 9 August 1787: correspondence from Petersburg, Virginia (p. 2/c. 3): "The Grand Federal Convention it is hoped will act wisely, for on their determination alone, and our acquiescence, depends our future happiness and prosperity; and if there lives a man equal to so arduous a task, it is a Washington."

¶ 17 August 1787: letter from "Meanwell" to Editor Eleazar Oswald (p. 3/c. 2): We have now sitting a Convention, which, I am persuaded, would have done honor to the states of Greece and Rome in their highest glory. Abstracted from their virtue, they have every additional tie of character, property and interest, that can bind men to be true to us and to themselves. Every honest man will readily agree with me in opinion, that our future political safety and happiness depend on the result of their present deliberations. This needs no illustration. I would therefore, through the channel of your paper, submit one query to the serious consideration of that honorable body, viz. Whether it would not be improper, at this crisis, [not] to dissolve themselves entirely, but rather to adjourn to meet again, if need be, at some future period?"

¶ 18 September 1787: notice of the closing of the Constitutional Convention (p. 3/c. 2).

¶ 26 September 1787: a member of Congress calls for an early Pennsylvania state convention to ratify the Constitution (p. 3/c. 2); reactions of various states to the proposed new frame of government (p. 3/c. 2–3).

¶ 1October 1787: Congressional resolution transmitting the Federal Convention’s report to the state legislatures (p. 2/c. 3); resolutions by the Pennsylvania General Assembly regarding selection of state convention delegates (p. 2/c. 3); an act specifying a new oath of allegiance for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (p. 3/c. 1–2).

Sotheby's is grateful to Seth Kaller for his assistance with this description.

PROVENANCE:Department of State (ink stamp, dated 23 June 1887 on first issue of the run) — Irwin T. Hughes (mid-twentieth-century inscription on old endpaper)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen