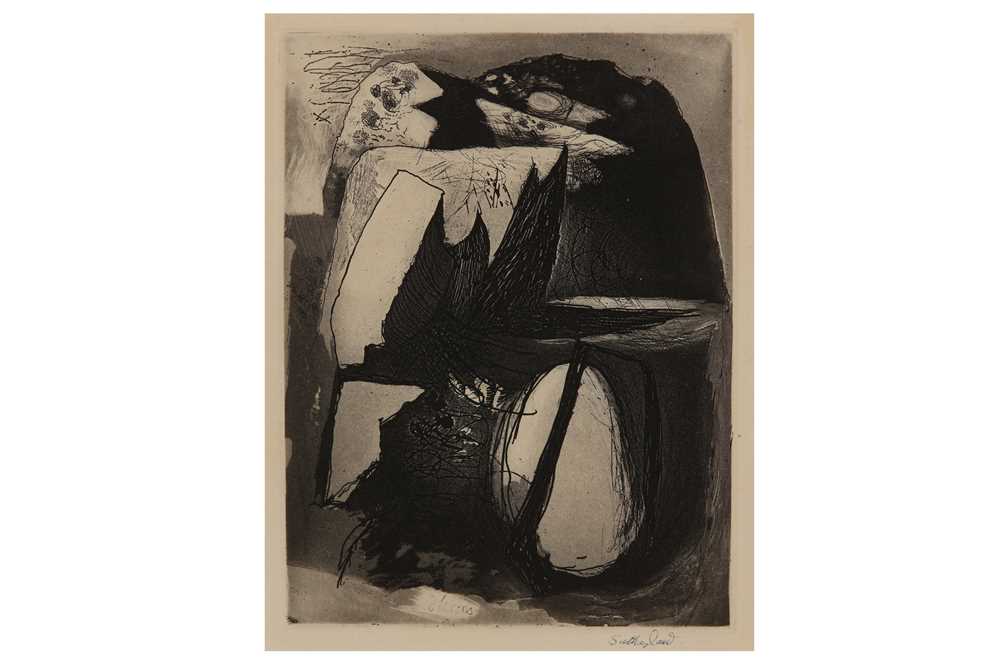

Graham Sutherland (1903-1980)

24 autograph letters and 7 typed letters signed to Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, West Malling, Kent, Cap-d'Ail, Venice and elsewhere, 1954-1964

Together c.80 pages, various sizes, one letter written on a postcard. Provenance: Sotheby’s, 21 & 22 July 1980, lot 165.

A notable series of letters to his friend and patron, the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, many relating to his 1954 portrait of Churchill, celebrated and disparaged in equal measure and loathed by the sitter himself. Several of Sutherland’s letters are written at the time of ‘the incarceration caused by my struggles to portray the P.M.’ – ‘in the evenings I have rushed home to try & put down on canvas what I remembered of the face & expression while I retained it in my mind’ – and many others deal with the sketches and Beaverbrook's ‘conception of a complete collection of Churchill studies’, listing their whereabouts, as well as those sketches which have been destroyed by Sutherland, details of their prices and discussions of the serious problems over the rights of reproduction caused by Churchill's dislike of the portrait (‘During the somewhat difficult period of the portrait and after, as I mentioned to you the other day, I have been at very great pains to avoid in any way aggravating the situation; I have consistently refused to permit reproductions, though I held the copyright of the studies, because I did not want to hurt such an admirable man’). Sutherland defends his painting as a truthful portrait of the man who sat for him: ‘The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning – "How will you paint me – as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently – except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet melancholy & reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better or for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. None the less he was self conscious & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded [...] I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as being a person who deliberated or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another’. Sutherland also offers advice to Beaverbrook on the formation of his collection (‘It is risky owing to the fact that John is an unequal artist, to buy anything unless you have seen the picture’); provides him with detailed ‘Notes on some [of his own] works in the collection of Lord Beaverbrook’; gives news of retrospective exhibitions and discusses publications on his work; comments on his other portraits (including those of Somerset Maugham, Árpád Plesch and Edward Sackville-West); reassures Beaverbrook that ‘I have no intention of writing my reminiscences – I don't even keep a diary’; outlines the aims of the Defence of Venice Exhibition, soliciting his support; and throughout the series expresses his gratitude for Beaverbrook's many acts of kindness,

In 1949 Graham Sutherland painted his first portrait, a startling full-length study of Somerset Maugham (now in the Tate collection). This powerful work, widely acclaimed, was followed by a portrait of Maugham's neighbour on the Riviera, Lord Beaverbrook (1952, National Portrait Gallery, London), whose newspapers did much to make Sutherland famous in Britain – not least when an all-party parliamentary committee commissioned him to paint Sir Winston Churchill as a gift for the latter's eightieth birthday in 1954. The result, both praised and reviled by MPs, was detested by its subject for making him look old and, he claimed, half-witted. It was subsequently destroyed on Lady Churchill's orders, though sketches for it survive. Among the best of Sutherland's later portraits are those of his friend Edward Sackville-West (1954), Paul Sacher (1956), Princess Gourielli (Helena Rubinstein) (1957, Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada), Prince von Fürstenberg (1959), Konrad Adenauer (1965, priv. coll.), and Lord Goodman (1973).

Graham Sutherland (1903-1980)

24 autograph letters and 7 typed letters signed to Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, West Malling, Kent, Cap-d'Ail, Venice and elsewhere, 1954-1964

Together c.80 pages, various sizes, one letter written on a postcard. Provenance: Sotheby’s, 21 & 22 July 1980, lot 165.

A notable series of letters to his friend and patron, the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, many relating to his 1954 portrait of Churchill, celebrated and disparaged in equal measure and loathed by the sitter himself. Several of Sutherland’s letters are written at the time of ‘the incarceration caused by my struggles to portray the P.M.’ – ‘in the evenings I have rushed home to try & put down on canvas what I remembered of the face & expression while I retained it in my mind’ – and many others deal with the sketches and Beaverbrook's ‘conception of a complete collection of Churchill studies’, listing their whereabouts, as well as those sketches which have been destroyed by Sutherland, details of their prices and discussions of the serious problems over the rights of reproduction caused by Churchill's dislike of the portrait (‘During the somewhat difficult period of the portrait and after, as I mentioned to you the other day, I have been at very great pains to avoid in any way aggravating the situation; I have consistently refused to permit reproductions, though I held the copyright of the studies, because I did not want to hurt such an admirable man’). Sutherland defends his painting as a truthful portrait of the man who sat for him: ‘The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning – "How will you paint me – as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently – except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet melancholy & reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better or for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. None the less he was self conscious & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded [...] I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as being a person who deliberated or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another’. Sutherland also offers advice to Beaverbrook on the formation of his collection (‘It is risky owing to the fact that John is an unequal artist, to buy anything unless you have seen the picture’); provides him with detailed ‘Notes on some [of his own] works in the collection of Lord Beaverbrook’; gives news of retrospective exhibitions and discusses publications on his work; comments on his other portraits (including those of Somerset Maugham, Árpád Plesch and Edward Sackville-West); reassures Beaverbrook that ‘I have no intention of writing my reminiscences – I don't even keep a diary’; outlines the aims of the Defence of Venice Exhibition, soliciting his support; and throughout the series expresses his gratitude for Beaverbrook's many acts of kindness,

In 1949 Graham Sutherland painted his first portrait, a startling full-length study of Somerset Maugham (now in the Tate collection). This powerful work, widely acclaimed, was followed by a portrait of Maugham's neighbour on the Riviera, Lord Beaverbrook (1952, National Portrait Gallery, London), whose newspapers did much to make Sutherland famous in Britain – not least when an all-party parliamentary committee commissioned him to paint Sir Winston Churchill as a gift for the latter's eightieth birthday in 1954. The result, both praised and reviled by MPs, was detested by its subject for making him look old and, he claimed, half-witted. It was subsequently destroyed on Lady Churchill's orders, though sketches for it survive. Among the best of Sutherland's later portraits are those of his friend Edward Sackville-West (1954), Paul Sacher (1956), Princess Gourielli (Helena Rubinstein) (1957, Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada), Prince von Fürstenberg (1959), Konrad Adenauer (1965, priv. coll.), and Lord Goodman (1973).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen