Property from an Important Swedish Collection17Chuck CloseKeith/Mezzotint1972 Monumental mezzotint, on Rives BFK paper, with full margins. I. 44 5/8 x 35 1/4 in. (113.2 x 89.4 cm) S. 51 1/8 x 41 3/4 in. (130 x 106.2 cm) Signed, titled, dated and numbered 7/10 in pencil (there were also 4 artist's proofs), published by Parasol Press, Ltd., New York, with the printer's blindstamp, Kathan Brown printed at Crown Point Press, Oakland, framed. Full CataloguingEstimate $100,000 - 150,000 Place Advance BidContact Specialist Editions@phillips.com

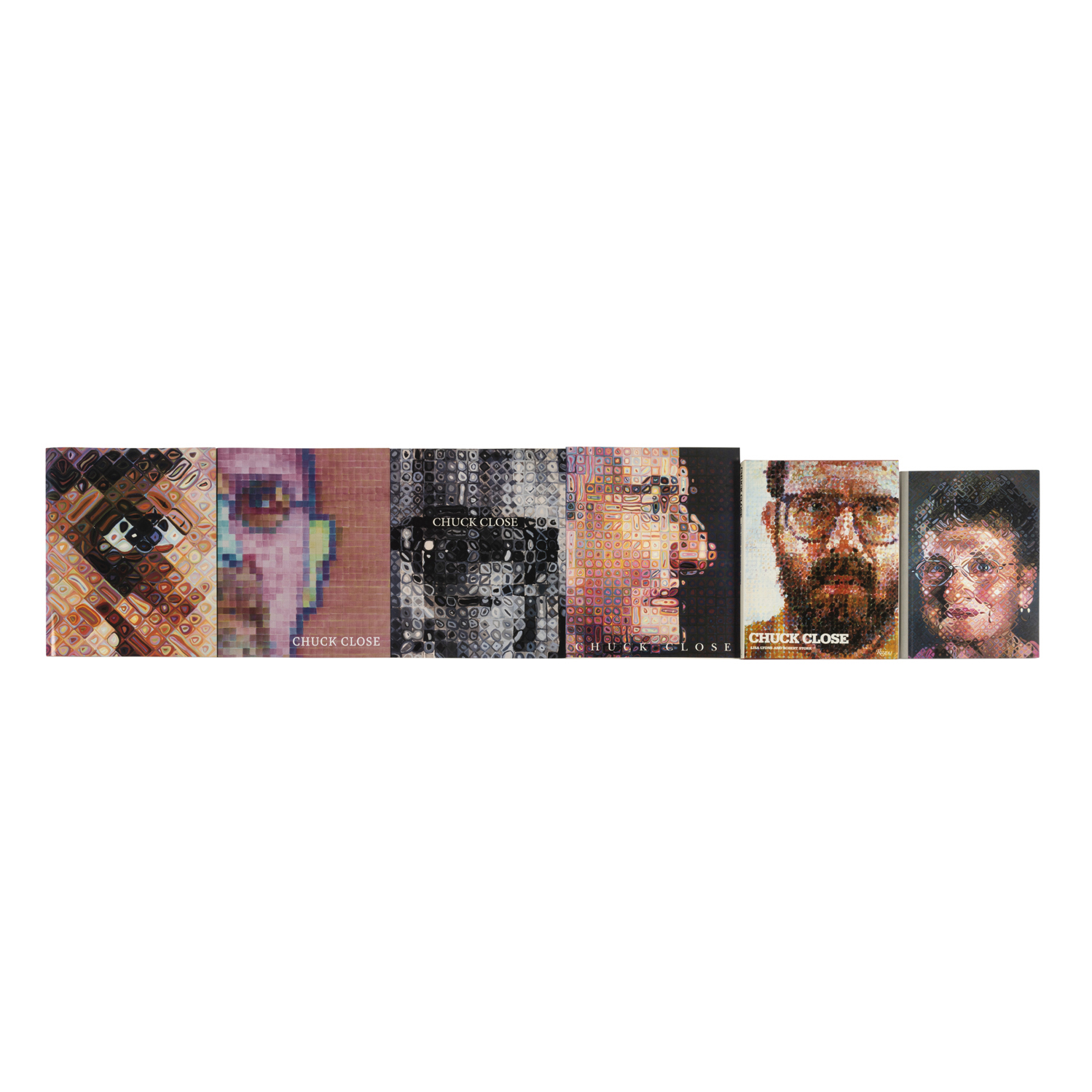

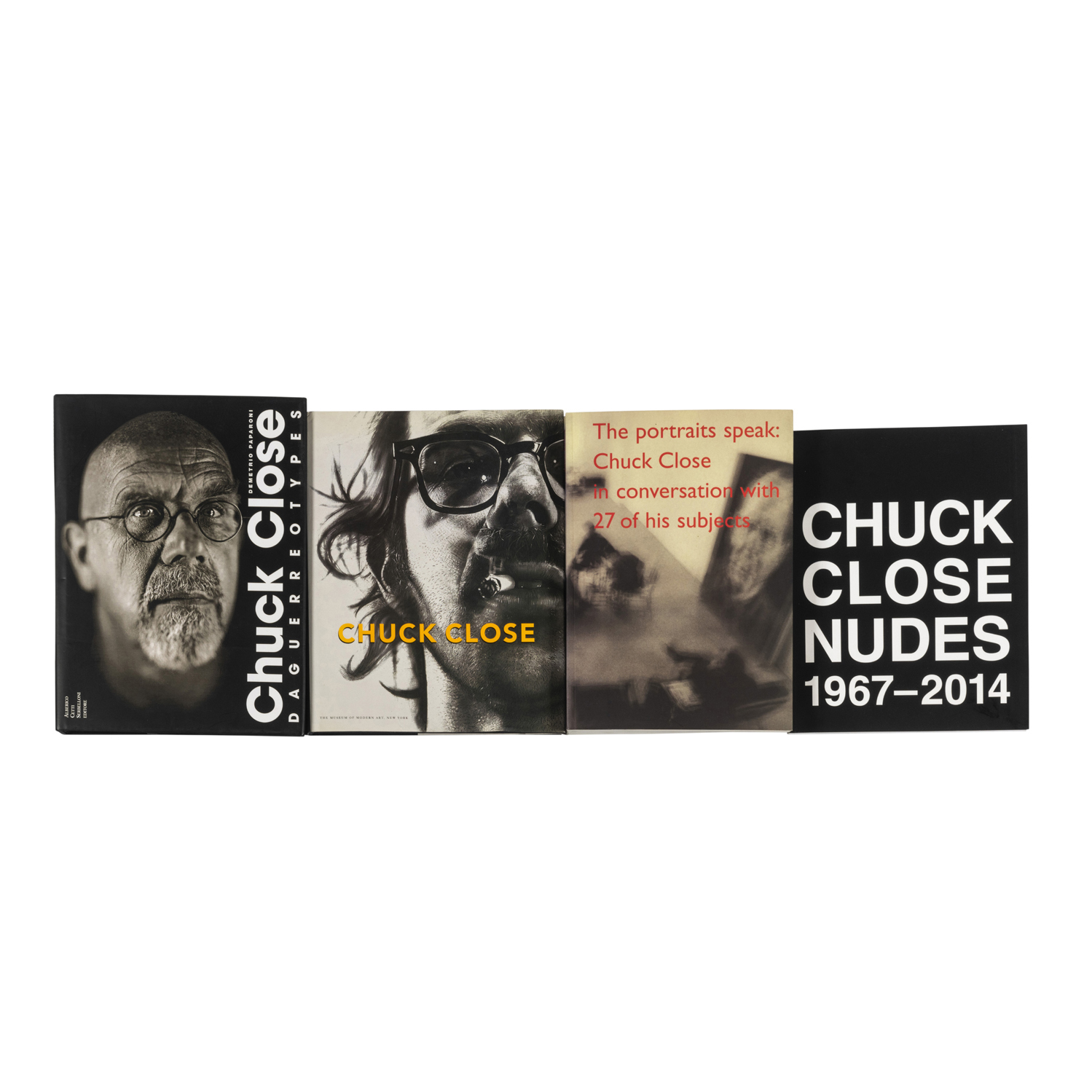

"After finishing Keith, I started doing [works] in which the incremental unit was visible and ultimately celebrated in a million different ways. That all came from making this print." —Chuck Close Writer and former Chief Curator of Prints and Illustrated Books at the Museum of Modern Art, Deborah Wye, wrote in her 1998 essay Changing Expressions: Printmaking of Chuck Close’s both adventurous and resourceful relationship with printmaking. Wye explained, “[Close] regards [printmaking] as an opportunity, a means to expand both his artistic vision and its expressive range.” Without hesitation or fear of technical restrictions, it was this intrepid attitude which led to the completion of Keith/Mezzotint in 1972 at Crown Point Press with founder and master printer Kathan Brown Close’s first foray in print was Keith/Mezzotint measuring three by four feet in ambitious size. Both in scale and technique, Brown remarked that “everything about the project was a challenge.” The largest print Crown Point Press had made with publisher Parasol Press, its size alone required that a new printing press be brought in to complete the edition. Despite this and the printer’s then inexperience with mezzotint, Close insisted that he and Brown make one at mass scale, fixated on this intaglio technique specifically for its intensely laborious process. Close said that he wanted to make a mezzotint simply because “no one had made one for a hundred years.” Since its height of popularity during the eighteenth and ninetheenth centuries, mezzotint had gone laregely out of style. “[I] wanted to do something that would require both Kathan and me to figure out how to do it at the same time,” said Close. “I love that kind of problem solving.” Working from dark to light, unlike an etching, mezzotint traditionally begins with a copper plate textured by rocking a steel-comb-lined rocker against its surface to create a toothy bite. When inked, as a result of the texture, the plate prints in a rich solid black, unattainable through other printmaking methods. A proof, depicting the painstaking mezzotint process of scraping away black. The photograph of Keith, and the grid within which Close worked. In Keith/Mezzotint, a photogravure process was used to transfer the image of artist Keith Hollingworth onto the plate. Close met Hollingworth while they were both teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. The portrait of Keith, who has facial paralysis, was taken in 1970 by the subject’s brother, Wayne. Close would come to refer to the photograph as a ‘mug-shot’ depicting all of his friend’s features in detail, from his pores to facial hair. After the image was transferred, Close worked on the plate methodically for two months, square by square, scraping and burnishing away parts of the plate’s texture to create areas of light, and thus image. The grid left behind, visible in the resulting print, reveals insight into its compositional structure and the artist’s process. Close said the following about this mezzotint: "I wanted the print to be more a record of an attempt to make a print. That’s why I scratched the grid into the plate and why the image doesn’t hold together as a whole as much as the paintings do. I didn’t want to disguise the fact that I made the print piece by piece—I didn’t want to try to shove it together and make it look mysteriously like one whole image afterward. The grid shows the increment that I was working with, the work-a-day problems of making the print. It was like making something out of bricks." Chuck Close working on Keith/Mezzotint at Crown Point Press, 1972 (Photo by Kathan Brown . Due to its enormous scale, Keith/Mezzotint was published in a small edition of ten and eight artist’s proofs. At the beginning of the plate making process, Brown recalled that “it was difficult for Close to imagine how a mark he made would print, and we pulled proofs every hour or so.” Pulling constant trial proofs by running the plate through the press

Property from an Important Swedish Collection17Chuck CloseKeith/Mezzotint1972 Monumental mezzotint, on Rives BFK paper, with full margins. I. 44 5/8 x 35 1/4 in. (113.2 x 89.4 cm) S. 51 1/8 x 41 3/4 in. (130 x 106.2 cm) Signed, titled, dated and numbered 7/10 in pencil (there were also 4 artist's proofs), published by Parasol Press, Ltd., New York, with the printer's blindstamp, Kathan Brown printed at Crown Point Press, Oakland, framed. Full CataloguingEstimate $100,000 - 150,000 Place Advance BidContact Specialist Editions@phillips.com

"After finishing Keith, I started doing [works] in which the incremental unit was visible and ultimately celebrated in a million different ways. That all came from making this print." —Chuck Close Writer and former Chief Curator of Prints and Illustrated Books at the Museum of Modern Art, Deborah Wye, wrote in her 1998 essay Changing Expressions: Printmaking of Chuck Close’s both adventurous and resourceful relationship with printmaking. Wye explained, “[Close] regards [printmaking] as an opportunity, a means to expand both his artistic vision and its expressive range.” Without hesitation or fear of technical restrictions, it was this intrepid attitude which led to the completion of Keith/Mezzotint in 1972 at Crown Point Press with founder and master printer Kathan Brown Close’s first foray in print was Keith/Mezzotint measuring three by four feet in ambitious size. Both in scale and technique, Brown remarked that “everything about the project was a challenge.” The largest print Crown Point Press had made with publisher Parasol Press, its size alone required that a new printing press be brought in to complete the edition. Despite this and the printer’s then inexperience with mezzotint, Close insisted that he and Brown make one at mass scale, fixated on this intaglio technique specifically for its intensely laborious process. Close said that he wanted to make a mezzotint simply because “no one had made one for a hundred years.” Since its height of popularity during the eighteenth and ninetheenth centuries, mezzotint had gone laregely out of style. “[I] wanted to do something that would require both Kathan and me to figure out how to do it at the same time,” said Close. “I love that kind of problem solving.” Working from dark to light, unlike an etching, mezzotint traditionally begins with a copper plate textured by rocking a steel-comb-lined rocker against its surface to create a toothy bite. When inked, as a result of the texture, the plate prints in a rich solid black, unattainable through other printmaking methods. A proof, depicting the painstaking mezzotint process of scraping away black. The photograph of Keith, and the grid within which Close worked. In Keith/Mezzotint, a photogravure process was used to transfer the image of artist Keith Hollingworth onto the plate. Close met Hollingworth while they were both teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. The portrait of Keith, who has facial paralysis, was taken in 1970 by the subject’s brother, Wayne. Close would come to refer to the photograph as a ‘mug-shot’ depicting all of his friend’s features in detail, from his pores to facial hair. After the image was transferred, Close worked on the plate methodically for two months, square by square, scraping and burnishing away parts of the plate’s texture to create areas of light, and thus image. The grid left behind, visible in the resulting print, reveals insight into its compositional structure and the artist’s process. Close said the following about this mezzotint: "I wanted the print to be more a record of an attempt to make a print. That’s why I scratched the grid into the plate and why the image doesn’t hold together as a whole as much as the paintings do. I didn’t want to disguise the fact that I made the print piece by piece—I didn’t want to try to shove it together and make it look mysteriously like one whole image afterward. The grid shows the increment that I was working with, the work-a-day problems of making the print. It was like making something out of bricks." Chuck Close working on Keith/Mezzotint at Crown Point Press, 1972 (Photo by Kathan Brown . Due to its enormous scale, Keith/Mezzotint was published in a small edition of ten and eight artist’s proofs. At the beginning of the plate making process, Brown recalled that “it was difficult for Close to imagine how a mark he made would print, and we pulled proofs every hour or so.” Pulling constant trial proofs by running the plate through the press

.jpg)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen